Interesting facts

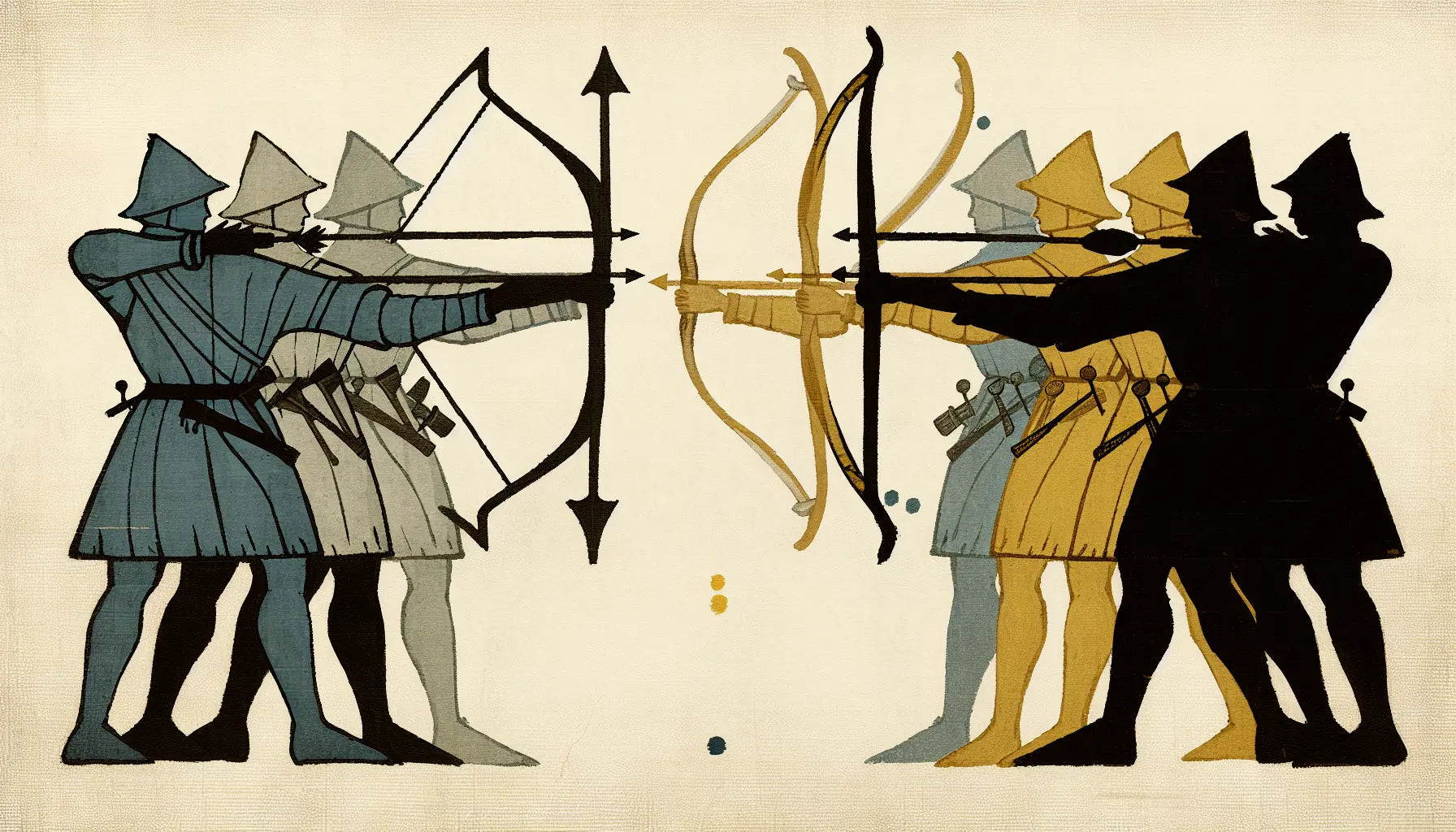

The use of ranged weapons in medieval England reveals a fascinating interplay between technology, tactics, and the harsh realities of warfare. Among these weapons, the crossbow and the longbow stand out as iconic instruments of ranged combat. While the English army is often celebrated for its remarkable skill with the longbow—particularly during the Hundred Years’ War—the question naturally arises: did the English army also employ crossbows, and if so, to what extent?

Crossbows in Medieval English Warfare

To begin unraveling this story, it’s crucial to recognize that medieval warfare was complex and continually evolving. The choice of weaponry depended on many factors, including the nature of the conflict, the terrain, and the availability and training of soldiers. Far from rigid, the makeup of armies shifted as commanders adapted to new challenges and opportunities.

Historical evidence clearly shows that the English army did indeed use crossbows, especially during the early 14th century. During the reign of Edward I, who led several campaigns into Scotland, crossbowmen formed part of the forces sent into battle. These soldiers served as ranged infantry, tasked with providing suppressive fire and supporting the heavily armored knights who dominated the frontline. Their presence is documented in muster rolls and payment records, shedding light on their recognized—though somewhat limited—role within English military ranks.

Tip: For enthusiasts of medieval history, exploring authentic artifacts like the beautifully crafted 'Bethlehem' - Medieval Crusader Silver Ring (12th-13th CE) offers a tangible connection to the past. You can discover this unique piece and more at auroraantiqua.store.

The Calais Garrison: A Case Study

A particularly fascinating example emerges from the Calais garrison. After Edward III’s successful capture of Calais in 1347, the English maintained a significant military presence there to secure the vital port city. Among the defenders were crossbowmen, who reportedly received higher wages than their longbow counterparts. This detail suggests that crossbowmen were valued members of the garrison, possibly entrusted with specialist tasks. The higher pay might reflect the technical skill required to operate and maintain the more mechanically complex crossbow, as well as the costs associated with its ammunition.

Advantages of the Crossbow

But why would the English, renowned across medieval Europe for their mastery of the longbow, choose to include crossbows in their ranks? What practical or tactical advantages did the crossbow offer?

The answer lies in the inherent differences between these two weapons. The longbow, traditionally made from yew or other hardwoods, was a demanding weapon for the archer. It required years of rigorous training and physical conditioning to master, demanding strength, precision, and stamina. In skilled hands, the longbow was deadly—offering a high rate of fire, impressive range, and formidable penetration power. Battles like Crécy in 1346 and Agincourt in 1415 famously showcased the devastating impact of English longbowmen on their French foes. Notably, many English archers were drawn from yeoman farmers or peasants who had practiced archery from a young age as part of royal mandates, making them a unique and surprisingly effective military class.

The crossbow, by contrast, was mechanically simpler in terms of the shooting process. Rather than relying on raw physical power and years of practice, it used a system of levers, pulleys, or cranks to draw and release the string. This meant a relatively untrained soldier could use a crossbow effectively after a shorter period of training. However, crossbows had notable drawbacks: they fired bolts more slowly than longbows released arrows, and their effective range was often shorter. Despite these limitations, crossbows excelled in particular situations—especially during siege warfare or when defending fixed positions. Their ability to deliver powerful, accurate shots even through armor made them formidable at close to medium range.

During the protracted conflicts of the Hundred Years’ War and the Wars of the Roses, the composition of English forces became increasingly diverse. On occasion, English armies enlisted mercenaries and foreign troops who carried crossbows and early firearms, such as handgonnes. These additions introduced fresh technologies and tactics into the English military tapestry, enriching battlefield options. The crossbow’s inclusion alongside the longbow reflected a practical openness to varied arms—not a stubborn adherence to tradition.

In many ways, the simultaneous use of crossbows and longbows in English medieval warfare demonstrates a pragmatic military mindset. Commanders certainly treasured the longbow’s superiority in open-field engagements, but they recognized the crossbow’s utility in specific contexts—where quick training, specialized roles, or siege circumstances called for its strengths. Crossbowmen could be rapidly trained and deployed as garrison troops or small detachments, supplementing the core of longbow archers or heavy cavalry.

The Adaptability and Role of Crossbowmen

An illustrative story from the Scottish wars highlights this flexibility. A commander facing urgent campaign timelines or relying on levies with little archery experience might well prefer longbowmen but knew that crossbowmen could fill critical gaps. Crossbowmen in the Calais garrison were reportedly paid more than longbowmen, a detail pointing to their valued role. This pay difference likely stemmed from the technical skill required to operate and maintain the crossbow, a more mechanically complex weapon than the longbow. Additionally, the production and maintenance of crossbow bolts incurred higher costs. Therefore, the increased wages not only compensated for these technical demands but also possibly reflected the specialist tasks crossbowmen were entrusted with, rewarding their expertise in managing these intricate weapons.Why were crossbowmen paid more than longbowmen in the Calais garrison?

Furthermore, the pay differences at Calais hint at more than just battlefield function; they point towards crossbowmen holding specialized skills and status. Beyond shooting, crossbows were intricate mechanical devices requiring upkeep and expertise. The heavy bolts were costlier than standard arrows, and proper maintenance could mean the difference between a hastily misfiring weapon and a reliable asset. Higher wages likely incentivized experienced men to cover these responsibilities, giving crossbow units a distinct role beyond ordinary archers.

By the late 15th century, of course, the widespread adoption of gunpowder weapons began to change everything. Firearms started to displace the longbow and crossbow alike, altering the nature of ranged combat dramatically. Yet for many decades before this technological shift, the English army’s arsenal included both bows in a complementary balance—a reflection of the changing face of warfare and the varied demands of the battlefield.

Broadening our view of medieval combat reveals that the English army’s engagement with the crossbow was anything but incidental or marginal. The common popular image of line after line of English archers unleashing waves of arrows obscures the true complexity of their forces. What actually existed was a rich mosaic of weapons, soldiers, and tactics adapted to different challenges over time. The crossbow—often overshadowed by the longbow’s celebrity—quietly contributed to the military success England enjoyed in the 14th and 15th centuries.

In Conclusion

One could liken the English army’s relationship with the crossbow to the work of a master painter blending a palette of colors on canvas. The longbow was the bold, dominant hue commanding attention and shaping the scene. The crossbow added subtle contrast and depth, filling in details and highlighting areas where its particular strengths were invaluable. Together, these weapons combined to paint a more complete and nuanced picture of battlefield effectiveness.

To sum up, the crossbow never replaced or eclipsed the longbow as the emblematic weapon of the English army, but it was far from absent. In specialized circumstances—such as the Scottish campaigns under Edward I or the strategically vital Calais garrison in the mid-14th century—crossbowmen played meaningful roles. Their inclusion underscores a critical lesson about medieval warfare: practical concerns and battlefield realities often outweighed tradition, and flexible use of resources determined the outcome of many conflicts.

Unveil History's Treasures

Discover NowThus, the crossbow holds a special place in English military history: neither grand hero nor forgotten footnote, but a vital thread woven through the turbulent centuries of medieval struggle. Its story is a reminder of the many hands and minds behind England’s victories, and of the ever-shifting strategies that shaped the course of nations.

Did the English army favor crossbows or longbows?

While the English army is famed for its use of longbows, especially during iconic battles like Crécy, crossbows were also employed, particularly in sieges and defensive roles due to their ease of training and effective short-range use.

Why did crossbowmen receive higher wages than longbowmen?

Crossbowmen often received higher wages due to the technical skill needed to maintain crossbows, which required more mechanical knowledge and costlier upkeep compared to the simpler longbow.

Where can I learn more about historical English weaponry?

To deepen your knowledge about historical English weaponry and connect with history, explore www.auroraantiqua.store, where you’ll find a range of authentic artifacts including the Bethlehem Crusader Ring.